Negotiating Gender:

The Boyish Bendings of

Sculptor Randy Polumbo

Catherine A.F. MacGillivray

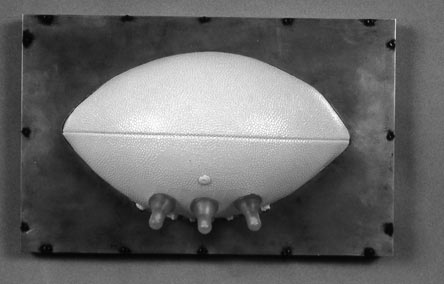

Sculptor Randy Polumbo`s work is playful, boyish, beautiful, mechanical, sexy and provocative. He uses a wide variety of materials, and has a special love for ball hitches, spare parts, movement sensors, objects cast in a variety of metals, and little items you can buy at the corner store, such as false fingernails and baby-bottle nipples; icons of sex and masculinity, such as condoms and Viagra tablets; and parts of his own body, such as his remarkably long toenails, which he uses as propellers in an animated piece of tiny proportions. Masculinity is a theme, too, in pieces that incorporate items like a football, a bowling pin, a baseball, and toy cap guns.

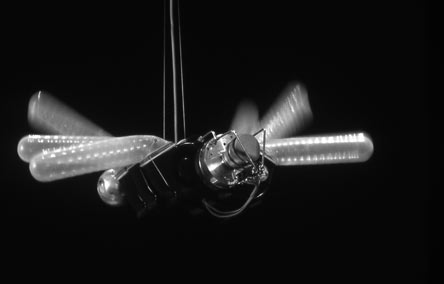

“Rover 4” trailer hitches, condoms, blowers 14” x 6” x 11” 2001 © Randy Polumbo

This is masculinity as culture presents it to a child, a boy child who then questions and subverts, who tweaks and transforms the tools of manhood to fit his own more androgynous––or bi-sexual in the Freudian sense (at once masculine and feminine)––nature. As Randy said once at a gallery talk on his work, “By placing the rubber nipples into the cylinder of the cap gun, I make it into my kind of gun.”

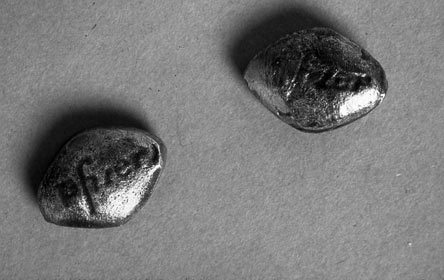

Another noticeable pattern in the work that I think also relates back to the vexed issue of contemporary masculinity is the apparent fragility of many of the pieces. Slight, sometimes jerky movements are achieved through various often low-tech means, and give an impression of sweetness rather than sturdiness. The delicacy of the pieces using Viagra mimics the finest of wrought jewelry, and indeed jewelry techniques and tools were used to make them. And who would have thought that Viagra could be so beautiful, so gemlike? The pills are big––and yes, this we could have guessed––but who knew their aqua-blue color was so exquisite, as are the metal appendages in Polumbo’s work that grasp and hold them?

The following interview between myself and sculptor Randy Polumbo took place on a sunny afternoon in Chelsea, New York City, on March 15, 2006. From here on in we will be identified by our initials, CM and RP.

CM: Randy, something that really interests me about your work is that initially it seems rather boyish, if I may say so, because of its use of machine parts and sports objects, toys and a sense of lots of tinkering having gone into it, associations one makes with boyhood, with what boys like to do. I also noticed the last time I was at one of your shows that there were a lot of young guys coming up to you and exclaiming that the work reminded them of tinkering type projects they used to entertain when they were younger, taking apart radios, fixing old cars and the like.

“Hotrod 1” pewter hot dog, quarters, pewter nipple 8” x 3” x 3” 2005 © Randy Polumbo

At the same time, your work bends these gender expectations by introducing “feminine” elements such as the nipples you so often use; I would even say there is a way in which the condoms you cast take on a feminine aspect; the way you fill the condoms emphasizes the nub at the end of them, their “nipple.” Or the way you set Viagra in such beautiful and delicate, almost jewel-like settings: the masculine medicine set in a feminine form.

I’m also reminded of one of my favorite comments that you made at a gallery talk last year, when you were explaining your piece that is a cast of a toy cap gun with a nipple protruding from it. You said that the addition of the nipple made it “your kind of gun,” referring to the way in which you complicate traditional masculinity, making instead some kind of “Randy Polumbo” gender hybrid that is uniquely your own.

All that said, can you talk a little bit about these themes in your work? About how you see your own gender being constructed in and through your work? The extent to which you see your work as critiquing or deconstructing traditional, which is to say patriarchal gender norms? You say in some of your press materials that you are interested in “libidinal economies.” Is this interest related in any way to what I’m talking about?

RP: I am always flattered and appreciative of your readings of my work; thank you. Yes, I have puzzled with the whole boy thing over the years, and what I am after is richness and complexity, not a one-note answer. I say this because it has been my experience that sometimes people look at my work and they want to find the punch line, which sort of reminds me of how people were trained by the conceptual art movement to expect a drum beat at the end––oh, there’s a mustache on the Mona Lisa, I get it––and so on. I think there is a lot of boy art that is erotica, or sentimental about boy things, or figurative work, and then there’s silly, juvenile boy work.

“Two Bits” solid silver Viagra cast .5” x .3”x .2” 2005 © Randy Polumbo

I like the idea of using all these registers in the service of what I hope will be a deeper study of the boy thing.

Regarding Lyotard’s idea of libidinal economies, I only recently discovered that book and I find it very interesting, the way he talks about the libido and its many economies or ways of spending, saving, investing, and wasting. I imagine most things are transactions of sorts. The fly has a deal with the spider, the moth with the flame, and life one with death. We barter and balance interests with ourselves and our companions, colleagues, and different institutions as well.

I remember in college studying all this stuff about sex and death, which was a relief for me, because it helped put some pieces together which had never quite fit before. Then came the deadly sex of the 1980’s from AIDS. It was a time when many people were quite literally consumed by their desire and appetite for substances or sensory experience. It also spawned some of the most amazing art and activism New York City has ever seen, like ACT-UP, and artists like David Wojnarowicz, who created very simple work that stunned by its beauty, and cold-cocked viewers with its blunt political messages simultaneously, and Nancy Dwyer, who can frame a simple question into an evocative and confrontational feast. This is when I got interested in condoms as an image, making flowers, space ships, and other organic abstractions out of them. Finding beauty, and also grounding it in “safe” imagery while it was becoming increasingly violent in its press portrayal, fascinated me.

“Harpy” trailer hitches, condoms, blower 5” x 14” x 5” 2005 © Randy Polumbo

Concurrently exists the sweet frailty, which is the boy thing you mention. The way knobs are shaped, the way bottles work––these are the veins I attempt to mine in my work. There is an exuberance to it when it is good. Society is so disassociated and lonely that there is this grotesque prosthetic use of inanimate objects to meet elemental and instinctual needs. So a smooth shift knob, a cold metal modern door lever, and a favorite bottle become grounding rods for a connection to other people and the planet. I will venture a step further, and say certain objects are almost like evolutionary silly putty, and we humans are drawn to mark them with our use. Thus boy energy is both grounded and broadcast like a radio transmission by boy things: the baseball bat, the convertible, the bowling ball, the rocket ship, the speed boat, the oil rig, the drill, the hole punch, and the bullet. This is where my work comes in.

CM: According to psychoanalysis, the practice that consists of opening something up to see how it functions, the impulse to go and see, to “look in,” what psychoanalysis refers to as the scopic drive, is a very fundamental one deriving from childhood, and from the child’s desire to exercise some control over the outside world, the bodies of others, especially the mother. So the scopic drive is about a search for knowledge and a desire to control. To what extent do you think your work functions at least in part in this manner? I’m thinking especially of the machine parts you re-juxtapose and re-contextualize.

RP: My version of looking in is probably more literal than you have in mind. There was a period when I thought I might actually be a machine, between the ages of 11 and 17, and I would make incisions in different parts of my body to A) see if blood came out and B) look for gears and wires and stuff and C) because it made me feel alive at a time when I was deeply depressed and shut down.

“Way Station” rubber, aluminum, wood, neon 16” x 10” x 6” 1998 © Randy Polumbo

I spent a lot of time alone as a kid, reading and taking apart and making things. There has to have been a lot of this kind of dissociative musing in our generation; many of my friends now and much current writing exhibit a kind of baby-boomer fugue state in certain areas, even though everyone is God-fearing, mortgage-paying folk now. But back in the day, I cannot even recall how many of my young contemporaries exhibited what would be considered extremely aberrant or self-destructive behavior. Again, this fit in with punk rock, neo-expressionism, and the Reagan years in New York City, a time when there was not a lot of hope. I had one spooky friend who would very carefully craft human figures out of play-dough with the internal organs rendered in great detail in play-dough colors he would categorize for this purpose. He would then shoot them with his BB gun, blow them up, or throw them off the roof, and next perform and document intricate autopsies on them. He’s a dentist now––and that gives me nightmares. As for me, I had a laboratory in my mom’s basement where I first started making machines from old record players and appliance parts. At one point I caused a mostly harmless explosion which nonetheless burned the bangs and eyebrows off myself, James Keely, Danny Foreman, and Harry Brosofsky. Needless to say, I had to find all new friends after that!

My earliest sculpture product was made when I was 9 or 10 from old record-player motors cobbled onto dismembered GI Joe parts. I would loosely connect a bunch of motors and appendages, wire them together with 110-volt house current, and they would usually run until they reached the end of their tether or connecting wires. They would ultimately short out, because I did not understand either the danger or impracticality of using crude, exposed wires. There would be sparks, occasional fire, and often the plastic would fuse together or heat into this thing that felt like it was still alive. I remember getting incredible comfort from these projects when they would run autonomously, and I would cry when they burned up.

When I was 11, I also had an insect lab and a program for delivering small explosives. While my peers were smoking pot, I was trying to revive dead insects with a car-battery-powered heart stimulator, and launching model rockets which blew up so vigorously, the parts would be spattered over a 4-block radius. I also made a large array of machines that were for inducing controlled behavior in bugs.

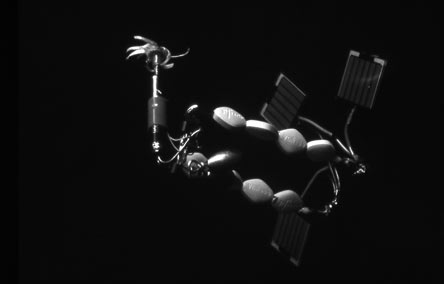

“Aurora Borealis” nail clippings, Viagra, solar cells, electronics 2” x 3” x 1”

2001 © Randy Polumbo

It sounds ridiculous and awful, but for example I had this motorized spinner and another one that was a shaker, where the bug entered the payload bay in a protective cocoon, and was manipulated by being shaken or spun. Then the bumblebee, large ant, or spider would be released and I would draw the pattern they traveled in, while also making an intuitive graph of the bug’s behavior.

I discovered how to make bumblebees fly in circles and for how long they would do so. I never killed a bug; I loved them, and prepared treats that various bug books indicated would please them. Not unlike my own childhood, there were these long scary stretches for my insect hostages, interspersed with little moments of sweetness.

CM: Explain more what you mean when you describe your childhood in this way.

RP: When I was growing up in the 60’s and 70’s, things seemed very black and white. I come from this crazy, violent, and addiction-riddled Sicilian family on my father’s side. For this reason, to go back to the question of boyness, my juvenile reading of maleness was that it was comprised not of the proverbial snakes and snails and puppy dog tails, but of lumps and bruises and bloodshed. As I became a young man, I hated and feared myself and my maleness, and actively tried to exorcise this aspect of my being. Being a premium sissy and momma’s boy, and hating things like sports, this came easily to me. Such a position was ridiculed by my father’s side of the family––though happily not by my mom––because I was not a very handy or worthwhile young man as measured by the Polumbo yardstick. According to this yardstick, if I listened to people I was ridiculed for being subservient. If I helped around the house, I was cheered on as a budding sissy who would make a good wife some day. These rigid gender requirements run really deep in families, like alcoholism, and other destructive patterns.

“Cold Fusion 1” solid 18k gold mosquito cast, 100mg Viagra, commemorative medal 1 3/4” x 1 3/4”x 1/5” 2006 © Randy Polumbo (background is studio view of casting prep)

I suppose I also felt battered by the expectations of my community and institutions insofar as male behavior went. I just could never get it right, and spent a tremendous amount of time getting beat up, pushed down stairs, and in various other ways re-playing and re-volunteering for the physical violence of my relationship with my father. Not surprisingly, I started to get very angry when I was an adolescent, but that quickly turned inward into various self-destructive behaviors, including drug and alcohol abuse, and the self-mutilation I mentioned earlier––I was one of those “cutters” that you now read about all the time, which is statistically unusual for a fellow. I mark puberty as the beginning of the self-mutilation years, when my focus and interest was in the onset of adult male physical traits. For example, when I first learned how to pleasure myself it was traumatic, because I felt like I was being subsumed by the enemy, almost like the zombie movies or alien flicks when the protagonist’s friends suddenly start to walk funny and their eyes change color––I assumed this new and scary pleasure was a gateway to eventual violent behavior.

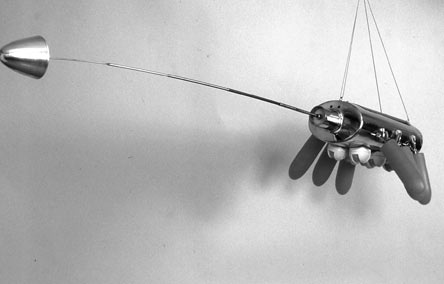

I’d like my work to be a celebration of the richness of all this gender miasma. It also can be kind of an automated, ritual exorcism from the terror of gender roles. As you mention, I particularly enjoy taking the most obviously phallic and macho images and turning them on their head or adding some duality to them. One of my favorite works is Probe 2, which is a giant car muffler festooned with what are essentially dildos. I cast silicone into condoms and made these particularly fat, almost baseball-bat like forms, which serve as legs for this insect-like creature. Sometimes they look like giant engorged ticks, or perhaps very ripe and voluptuous fruits. Nipples are made of infrared motion detectors, and a polished metal nose cone extends and retracts over 5 feet, which changes the balance of the entire piece––the angle at which it hangs changes as the nose goes in and out. It is funny when you see it at first, and has a strange, almost bovine quality, with its infrared udder formation and its supple, sturdy “legs.” Some adults find it a little unsettling, but kids love it. In fact, it spent a year in a children’s museum––this thing festooned with motorized dildos––smack in the middle of the main exhibition hall, but the kids were probably oblivious to its sex-related qualities.

“Probe 2” chrome muffler, rubber condom casts, sensors 24” x 20”x variable”

2000 © Randy Polumbo

CM: That’s wonderful—and I use the word “wonderful” with care; I think your work in general can be said to evoke a great sense of wonder and wonderment. Wasn’t it Descartes who said that wonder is the first human passion? I think he says something further as well, like “and this passion that is wonder has no opposite or contradiction and exists always as though for the first time.” I have felt this way when experiencing your work, and I have seen this on the faces of others when confronted with the Randy Polumbo product. But to get back to discussing your journey, can you talk a little bit more about the origins of your art and of your creative drive? Other ways in which it started in childhood perhaps?

RP: When I was a really little kid, I felt like I was jammed into this tiny space, the kind perhaps a worm would occupy. My father was violent, and at different times from the ages of 0-7 I was beaten severely for things like breathing incorrectly, or standing the wrong way. By the time I was 5, I was experimenting with my own ability to control my environment and to make various environmental manipulations, like holding my breath until I passed out, or punching the cottage-cheese textured wall in our military-base home until blood came out of my knuckles, and then logging in my notebook how many punches it took––I was never without a notebook. Creating even the appearance of having some control over my environment, with accompanying documentation, gave me this early sense of imposing order that is still important to my work today. Bleeding for me was always kind of a relief also, cementing my aliveness with inarguable proof of organic activity. While I left these behaviors behind two decades ago, along with drugs and alcohol, I remember feeling at the time that they were like small victories in a war I have since won.

“Ham Blossom 1” condoms and ham can casts, resin, LED lights 14” x 9”x 6”

2006 © Randy Polumbo

This type of manipulation-as-coping took the form of other odd rituals of self-documentation. Again, these exercises proved my existence, and also sometimes demonstrated my influence over others. For example, I would survey the house and turn all the soaps over and out of alignment with the soap dish by precisely 5 degrees. Since I felt so powerless, I imagined I was controlling other people by making them change the angle of their soap approach, and thus, almost like a geometric theorem, causing them to subconsciously know I existed. If I turned the Soap towards direction B, and C touched the Soap, then I touched C and made them turn via the soap. I also had a thing with screw heads, wanting to turn them all to 12 o’clock––this of course was in the day of the slotted screw. Such guerilla-decorating techniques continued until I was in my 20’s, and today I build extremely meticulous interiors for a living. So in the end I have managed to turn this energy into the fuel for a reasonably successful business, which is another example of the alchemy my work is about. Also, I don’t think it is an accident I meandered from studying art at Cooper Union into construction, one of the most obnoxious and testosterone-charged work arenas. When I started out, I was afraid to even speak to men, or to eat in front of people, but I liked building things. Somehow, working through all this was healing psychically, the same way getting into recovery from various addictions has been.

CM: I like that articulation, “guerilla-decorating techniques.” Can you give other examples of what you mean by this?

RP: Well, let’s see. Did you ever read that Dr. Seuss book, Horton Hears a Who? These early attempts to be seen and heard I was just speaking of remind me of that story, which was always a favorite of mine as a kid. Similarly, the so-called earth work of the 70’s– the huge bulldozer art in the sand out in the desert done by people like Richard Long and Robert Smithson––also reminds me of the efforts of the Whos to be heard. Another favorite was The Velveteen Rabbit, to which I made a video tribute, riffing on the stuffed rabbit becoming real when its eyes and fur wore off. In it I drew my blood into a big syringe and shot it up into marshmallow bunnies––you know, the kind you get at Easter––until it spurted out of them in different places.

“Rover 2” rubber condom casts, electronics, sensors 9” x 7”x 6” 1999 © Randy Polumbo

At one point I was obsessed with the little water jets that blow cleaning fluid onto windshields, and modified them so they sprayed outwards. Thus they became what I imagined was a weapon for shooting at pedestrians at crosswalks. I did this to “volunteer vehicles,” then ran away and just imagined the outcome. I also developed a small, electronic device that would harmlessly shock anyone who peed on it illicitly, right on their organ through the urine stream, because it bothered me in NYC that men peed in certain places, and imagining I could police the input/output situation really fascinated me. SoHo was so sodden in pee it used to be plastered with these spray-paint stencils that were great, featuring the international circle and slash across a pictogram of a man peeing with a growing puddle at his feet.

CM: How does this, if at all, relate to your current use of Viagra tablets in your work?

RP: I see Viagra as an evolutionary fuel cell, the same as the solar cells, rubber nipples, and rubber and lambskin condom castings I also use in my work. Viagra reminds us that the male physical plant doesn’t work as well as it once did. Testosterone and sperm count are way down. Kind of like the newts, frogs, and lobsters that are all disappearing inexplicably.

Again, the idea of input and output exchanging or being fluid is another aspect that intrigues me. Nothing is black or white, male or female, on or off. In fact, I think the notion that we can control the in-and-out is a fetish that is almost pornographic. To me, instead, the idea that there is a little bit of everything in everything, like good cooking, makes life richer and more human. It can be frightening, but beautiful.

“Lighthouse 1” glass gun, found rusty cans, electronics, solar cells 9” x 7”x 6”

2004 © Randy Polumbo

CM: Your work has been compared to Duchamp’s because of its reliance on objets trouvés, found objects. How do you see yourself in light of Duchamp and his work? Do you credit him as a precursor and influence?

RP: I heard about Duchamp in high school, being a bookworm also, but his art never really interested me that much. Duchamp was historically relevant no doubt. At the same time, because he was an early collagist and juxtaposer, I think he got more attention than some of the work seems to me today to merit. I did make a self-portrait in my youth that was an homage to him, a pair of those nose-and-mustache glasses placed on my penis and shot close up using Polaroid SX 70 film; remember the folding camera? I have read some of Duchamp’s writings, and wonder sometimes if he wouldn’t roll over in his grave that no one today gives a merde about his paintings, and he is mostly remembered for the famous urinal.

CM: Yet, like Duchamp, you do incorporate a lot of unexpected objects into your work, as I have mentioned before, and I would especially note their unusual juxtaposition to one another. I am thinking in particular of my own delight when I noticed that for some of your propeller blades you use toenail clippings; for others you use fake fingernails. My delight came from not immediately recognizing what they were out of context, and then when I finally figured it out, being so pleased by the imagination and whimsicality of your choices—again, there’s that Cartesian sense of wonder I mentioned earlier. Anyway, would you agree that these are, strictly speaking, found objects? Or perhaps instead some kind of riff on the use of found objects? How do you choose your materials and what does that process mean for you and your art?

“Food Chain” silver, lead, cast glass, buffalo nickels, Viagra 12” x 8”x 20”

2005 © Randy Polumbo

RP: Thank you for your generous description of one of my favorite visual devices. No question these are found objects, but usually they are manipulated, pruned, dissected, and recombined to the point where you need to be up close to recognize them. Like a mirage, these pieces fall apart from one angle, then build together into something else. On closer inspection, the small spaceship model becomes an old condom with fingernails glued onto it. Is that Cubism? And in a way, yes, here we are, back to Duchamp again.

CM: Are there others you would also credit as influences? If not particular artists, then perhaps movements or other kinds of learning or life experiences?

RP: If I had to name influences it would start with the three R’s: rock-and-roll and reading. I was unable to sleep more than a few hours a night until I hit my thirties. When I was a kid, I would read under the covers with a flashlight, and need to change batteries twice sometimes. I would stay up all night picking the guitar, scribbling in journals, and reading. I found a 45 RPM of Patti Smith’s “My Generation” in 1977 at a yard sale, and this clued me in to punk rock. Instantaneously my alienation was tempered with this great proof that good things could be born of it.

Smith’s version is very different from the Who’s version, in that she screams like a butchered animal throughout, and splices a rhyming jingle of expletives into a pre-chorus; my kind of Who song! Another one I love is that crazy song “Perfect Day” by Lou Reed. It is so goofy; it is almost embarrassing to listen to. The singing is off-key; the melody whimsical and singsong; the drama of it ham fisted; it seems like the worst song in the world, but it sticks with you. Everyone likes it. There is something about it that is also soulful and stately, because it is not afraid to be all these things at once, shamelessly. I found a crazy version of it on the Internet sung by Bowie, Pavarotti, Bono, and half a dozen other luminaries; it is insane in its exuberance, and the perfect antidote or salve for today’s world. I want my work to be like this.

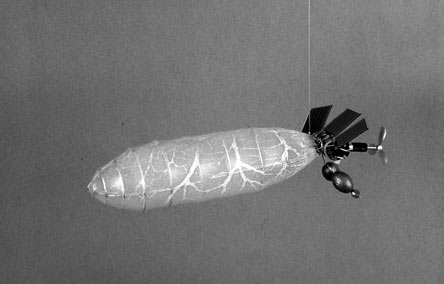

“Manifest 2” condom, solar cells, electronics 10” x 4”x 4” 2000 © Randy Polumbo

My hope is that a twitching thing made out of an old lambskin condom stretched over a wire blimp frame, with red fingernail propellers powered by a tiny solar array, could get you in that same spot and hook you. Hey, it is not an accident that my work also shares aspects in common with fishing lures, fishing being another fetishistic and ritualistic practice I am absorbed with, speaking of symbolic hunting and gathering.

But to return to your question about influences, here is another. I was in a mental hospital as an inpatient for months at one point in high school, and under heavy medication for much of my adolescent years—until I became a daily drinker and drug user; then I did my own medication, which was better than the Thorazine I was given by the doctor in the 1970’s. At the inpatient facility I had this neighbor on my hall, Lucy. She did not speak English—she was Portuguese—and was about 1000 years old. She would sneak into my room and take trash from my waste baskets and arrange it by size, based on a type of thematic reasoning—paper with paper, sharp with sharp, clear with clear—and work for hours adjusting the spacing and composition.

When I would come to my room and find her there, she would just smile and smile, so proud of her work that no words could even describe it. I immediately saw in her a compatriot. She took great pleasure in making something lucid and beautiful and orderly out of someone else’s waste. I eventually discovered I was not her only patron; everyone let her in their rooms to do this, though we were not allowed to have people in our rooms. What moved me most was her universal appeal and how she traveled freely into closed areas and touched everyone. Something jelled for me then, and I quit painting and drawing so much and started making little collages and mechanical devices; I imagine these were cousins of her work, thematically and structurally.

“Duplex 2” Silver cast of artist mannequin & rubber baby bottle nipples 7” x 3”x 3”

2005 © Randy Polumbo

I tend to draw ideas from nature too. I have always been curious about plants and science and the idea that people are very complex organic machines, for example. There is this phenomenon that is often illustrated by use of the Mandelbrot set—that hackneyed fractal that appears on t-shirts now––the concept of scalar symmetry. The way this works is, you zoom in on some little paisley shape, and it has bumps on it. Then you zoom in on the little bump, and it becomes a paisley shape. Then of course when you zoom in on that, there are the little bumps again, and on and on, repeating infinitely.

Be it certain seeds violently exploding from their pods or mankind boosting satellites with a suspicious payload of Beatles’ songs, the human genome, and some classical literature aboard, like with scalar symmetry, it all just seems the same to me, to infinity. I might also add that some of the complex reactions the earth has issued lately seem like they could be immune responses designed to cleanse it of human—global warming as a sort of fever and natural disasters as a type of sneeze.

CM: I like the image you share of the seed pod. I think Derrida uses the same image as an example of what he means by his term dissémination. The way language generates meaning via an endless chains of signifiers is like a seed pod exploding, sending its seeds floating everywhere and anywhere, resulting in what Derrida calls an ultimate deferral of meaning or the dynamic instability of language. It seems to me, come to think of it, that your work has other things in common with deconstruction. What do you think?

RP: Well, as I have said, I am definitely fascinated by pairings that appear at their onset to be contradictions but aren’t. The ugliest articles can be the most beautiful, like the foulest cheese can resonate most handsomely on the palate if paired with the right green apple or cracker. I wonder sometimes if the failure to recognize how close together the poles are is the cause of some of the disconnects in our world. People seem to prefer things in black and white.

“Six Pack” plaster, aluminum 12” x 10”x 6” 1998 © Randy Polumbo

CM: It’s interesting how we have come back to where we started in a way, in that we have returned to the issue of deconstructing binaries, favoring the logic of the continuum over that of the paired, hierarchized opposition. This was the initial point I wanted to make about the way you construct gender along a masculine-feminine spectrum, and now I hear you saying that this is a commitment in your work that extends to many other areas as well. So to answer my own question, I would say you’re a true deconstructionist Randy, in the original, Derridean sense of the word!

RP: What do you mean by the true, Derridean sense of the word deconstruction? Can you unpack that for me Professor?

CM: Gladly, since to do so will allow me to bring up one of my pet peeves—the way the word deconstruction has entered colloquial speech as a synonym for analysis, so that people talk about how they are going to “deconstruct” something, when all they really mean is that they are going to analyze it. That’s not what deconstruction means! Derrida means something very precise by the term, and it has to do with just what you hope to accomplish with your work it seems to me: showing how the hierarchical binaries around which we organize our world and in which we believe so fervently are in fact ideologically-motivated illusions. Everything contains, is defined by, and therefore is dependent on its opposite, making life and meaning fluid rather than fixed––or, as you have said, “nothing is black or white, male or female, on or off.”

And since we have come full circle, perhaps this would be a good place to end? Like most endings, ours will be somewhat arbitrary, in that there are many other aspects to your work that we haven’t even touched on, such as its inherent Americana-ness, but I wanted to focus on issues of gender, since that is my own personal field of interest and expertise.

RP: Thank you, Catherine, for your nuanced and kind appreciation of my work. It’s always a pleasure to talk about my art with someone like you who is so outstanding in her own field; it makes me think and realize things about myself and my journey that might otherwise never have fully come together or made sense in just the right way. Did anyone ever tell you you should be a psychoanalyst?!